Q: Tell us a little bit about yourself, and what you’re doing here in Juneau.

A: Hello, my name is Randy Reyes. I am the director of The Brothers Paranormal and this is my first time in Alaska, from Minneapolis, MN!

Q: How did you first become involved with Perseverance Theatre?

A: Well, Leslie Ishii brought me to Perseverance Theatre. Leslie has been a colleague of mine for a long time. We started working together as part of the Consortium of Asian American Theaters & Artists. I was part of putting together the production in the Twin Cities, a co-production between Penumbra Theatre and Theatre Mu, directed by Lou Bellamy. This was another opportunity to do the play. And Leslie was in that production, so when she asked if I wanted to direct this production, I asked her if she wanted to be in this one as well, and she said yes. So I’m just very excited that she’s going to be in the show and that she invited me to direct it here in Alaska, in Juneau, which is a gorgeous beautiful place that I’m totally in love with.

Q: Prior to the shutdown, when were you last able to be in a theatre?

A: Since the shutdown, I’ve done theatre projects. One was a theatre dance project that was not fully produced. It wasn’t a play, so this is the first play in a theatre that I’ve done since the shutdown. And the other was a play set in a zoo.

Because of the new surge, we started this rehearsal process via Zoom. Yeah, it’s very emotional actually. It’s great to be back. It’s great to be back in a theatre, great to be back in the process of creating, in putting up a play. I’m ready. I’m too ready. I’m so excited that I’m beside myself!

Q: What does it mean to you to be returning to creating in the theatre?

A: When the lockdown happened, I was trying to figure out how to continue to do theatre, and a lot of the theatre that was being done was through Zoom. And in the midst of that, living in Minneapolis, where George Floyd was murdered, and that really made me question what I should be doing as an artist. What kind of stories should I be telling? What kind of communities should I be lifting up? So I went into a little identity crisis during that, and then started to write more and do some Zoom things. But that was not theatre to me, it’s video. It’s not a live audience so it wasn’t theatre. And I had to take time to mourn that. To mourn theatre not existing for a while. Having it come back means everything.

I’m very excited to be in the same room with actors. So many things happen in the room together, so many discoveries are made that are limited when you’re in a box, a zoom box. And then the audience, that’s another huge part of theatre is live audiences and how that affects the production. But I think I’m most excited to come back with a play like The Brothers Paranormal, a story of a Thai family and an African American couple. It’s a story about home. It’s a story about what haunts you, about trauma, about displacement, about climate change, and mental health… So to be with a cast as diverse as this, with a production team as diverse as we have, in a place, Perseverance, where Leslie’s really emphasizing a culture of equity and diversity, justice and inclusion. It is an honor, it is so exciting, it’s a great way to come back! I wouldn’t want to come back to do anything else. Like if I were to come back to do a regional theatre production of A Christmas Carol, it would be fine, but to come back to this, especially in this magical place, Juneau, AK, it’s a great honor.

Q: And we’re honored to have you. Talk to me about some of the themes that struck you in this story, The Brothers Paranormal.

A: The thing that struck me initially when I first read the play by Prince Gomolvilas was the genre of horror, right? I was like, “Oh my gosh! Who writes live theatre in the horror genre?! I love that! I love the idea of being able to scare someone in a live setting. That was my initial response. But the play is so much more than that.

And then you have the Thai family who are dealing with issues around immigration, displacement and mental health. You don’t see a Thai family represented in television, film, theatre in America, so that’s very exciting. And then you also have African American representation with the couple also dealing with displacement and mental health. So to have those two ethnic groups in the same play when you’re talking about the things that haunt you, and all the parallels between those two communities…it was the most unique play I’ve read in a long time and I am so committed to having this story told and to having people hear this story, not only the general public but especially from the Thai community and the Thai American community. To be able to see their story being told is very important.

Q: How can audiences expect to see these themes come forward in your work?

A: I did classical training as an actor at the University of Utah, and then went to Juilliard where I graduated in 1999 and throughout that whole time, I’d never been in a play where I played an Asian character. I’m Filipino American. So I had a really skewed idea of what kind of artist I was, and I thought I could do classical work. I didn’t know what I didn’t know, and I was naive in that way. But once I graduated from Juilliard, I had an agent, I was auditioning, and I realized I wasn’t getting the same opportunities that my white counterparts were getting, and it didn’t matter that I didn’t feel like I was limited by being Asian…everyone else did. So I really had an identity reckoning where I had to find a way to embrace who I was.

It wasn’t until I was cast in a workshop of Flower Drum Song that David Henry Hwang was doing, that I was part of an all Asian cast for the first time ever. And it was a different energy. It was a whole different game! I don’t know how to explain it other than saying there was a sense of family that I’d never had before. There was a sense of understanding, there were shortcuts… It was just an easier room, and how I fit in that room was also very different. And that’s not even a Filipino character. The first Filipino character I played was Magno in The Romance of Magno Rubio, and that changed my life. that was like, “Oh, this is my culture! I am an expert in this. I don’t even have to try. I don’t have to research. I just am. There’s language in it, there was movement, we did stick fighting, we sang in Tagalog… I was born in the Philippines so that changed everything. Suddenly I wasn’t acting, I was just being, and felt completely comfortable within that. And I realized that in other times, I was acting beside myself. I was acting apart.

I teach acting and I do this exercise where I have the students imagine their character. I remember doing this in a college, and I was having the students imagine their characters, what the character looks like, their hair, what they’re dressed as, look at their hands, all this, their eyes. And I’ve never said this before, but in the moment I said, “Ok, look at their ethnicity. What is their ethnicity?” And I realized in that moment that every character that I had ever played I had imagined as white, and I almost had a breakdown right there. I wasn’t using myself! I was not authentic to myself. I was acting like something rather than being. And from then on, my acting changed dramatically. I had to start from me. I was in A Christmas Carol and I had to figure out why I looked the way I did and why I was in A Christmas Carol. Any show, I had to start with the way that I look and justify that, find my backstory, and then I could move forward.

But that’s how that all started. So I think that’s why I’m so committed to this… We have three Thai Americans in this cast which is unbelievable, and I just want them to be able to bring themselves to the piece. To me it was life changing and totally changed me as an artist, to be able to play my own ethnicity or feel myself, feel comfortable to just use myself. And I know there’s a lot of actors that never even have to think of that. It’s just assumed. So yeah, I understand that journey, and I’m excited to share that journey with this cast.

Q: And we’re excited as well, thank you. Okay – now some lighter questions: what is your favorite scary movie?

A: I think my all time favorite scary movie is Pet Semetary and I don’t know why. I think that animals and kids who haunt people, freak me out. I used to watch The Twilight Zone and yeah, I’ve always been freaked out by when kids and animals come back to life, more than adults for some reason! And then The Ring really freaked me out. But I feel like where I was in my life when I saw Pet Semetary, it scared me in a profound way. Yeah what’s the one with Jack Nicholson? Yes, The Shining, because that was more psychological, and I think that if you ask me what really scares me, it’s how dark the human psyche can get. And that freaks me out more than gore. To see how dark a human can get, especially to their own family…that’s horrifying.

Q: Which is scarer to you? Ghosts or vampires?

A: Ghosts.

Q: Ghosts or aliens?

A: Ghosts.

Q: Ghosts or zombies?

A: Ghosts.

Q: Ghosts or psycho killers?

A: Psycho killers.

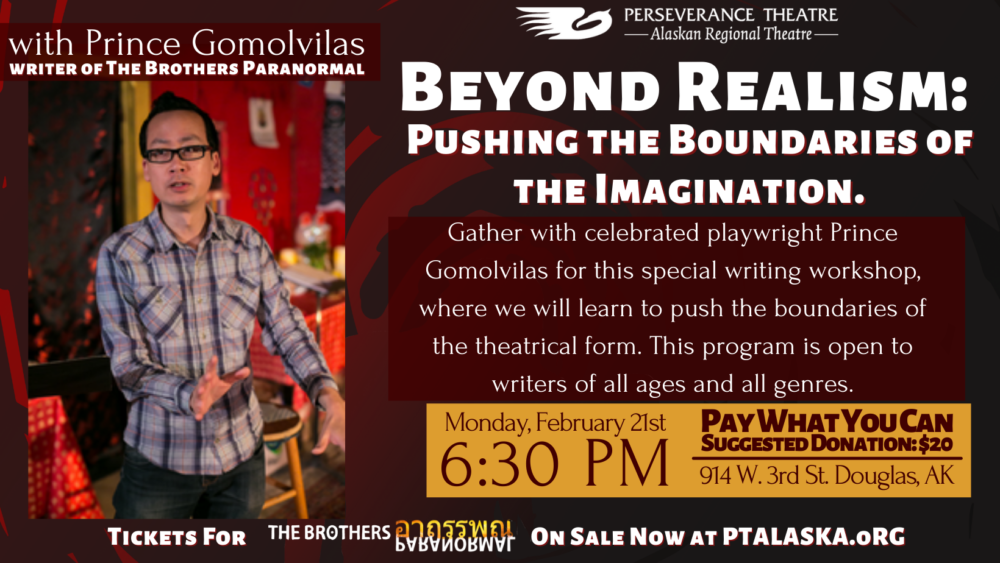

To learn more about Perseverance Theatre’s production of The Brothers Paranormal and to purchase tickets, visit ptalaska.org/tbp.